On a sunny Friday afternoon, I found myself opposite the black façade of Paradise. As the restaurant was closed, all I could see inside were concrete walls and wooden chairs. When you step through the doors however, you quickly notice how thoughtfully the décor is designed, blending wood and concrete, inspired by one of the great Sri Lankan architects, Geoffrey Bawa. There, I find Dom Fernando, owner, creator, and executive chef of Paradise, welcoming me in wearing his signature leather apron and dashing smile. He takes me down some narrow stairs to meet the team in the small but perfectly organised kitchen. I immediately start taking pictures, he’s showing me some of what has already been prepared, giving me a taste of a sea-buckthorn jelly used as part of the set menu’s dessert.

Tristan: So, Dom, how did you get in the kitchen in the first place?

Dom Fernando: I’m not a professionally trained chef; that’s the first thing.

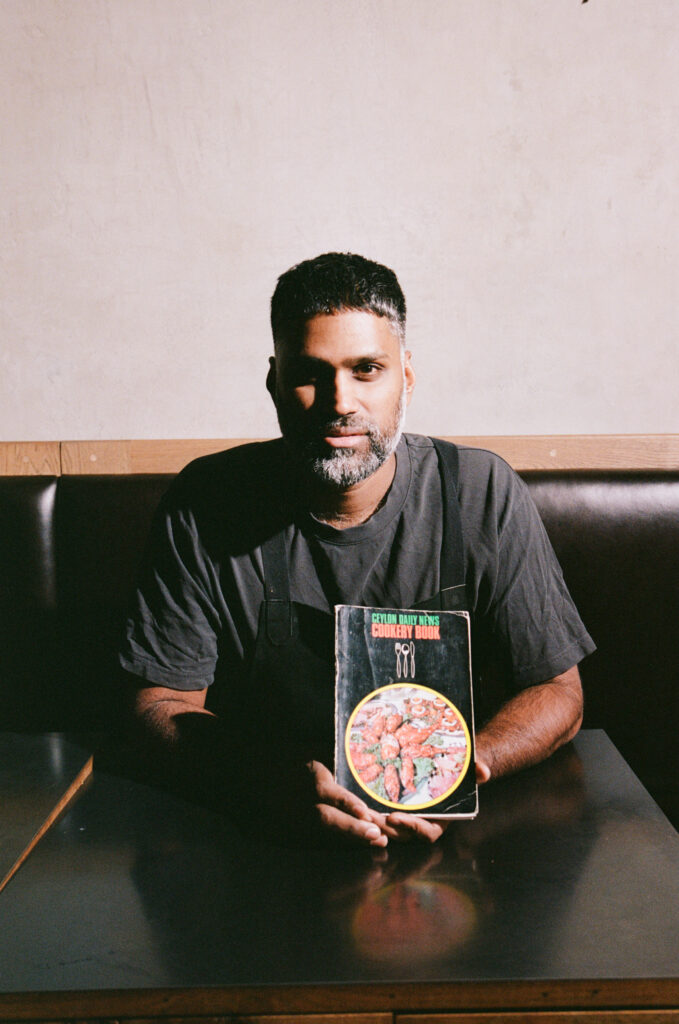

I learned to cook for my grandmother when I was 16, 17,18. Food was always a big part of our culture and our community. Actually, there’s a book up here [he points to the shelf under which he is sitting], called the Daily News cookbook. It is the first Sri Lankan cookbook. This is an original. This is what my grandmother bought in 1940-something, this exact book, and it’s how she learned to cook at age 17. She learned to cook from this, and then she was the matriarch of our family, and so I learned from her as well as my mum and my mum’s sister.

Food has always been a passion, and I’ve always just enjoyed social cooking. But I had a corporate career, and then I left it in 2019 and opened Paradise.

I developed the menu when we first opened, but I’d never really thought of myself as a chef; it was a vent. It was an area in which I was able to just use my creative skills.

Then we had a couple of head chefs, et cetera, and then it got to a point where I wanted to move away from having a head chef and stay heading this myself.

I was thrown into it during service one night, and I learned very quickly.

And I spoke to Ajo, who is the owner of Akoko and Akara, and we were both in the same predicament, and we were discussing what we should do, and he said I’ve just been to cookery school, and I think you should do too. So, I went part-time, spent my daytime at cookery school and the evenings, worked in service here.

I just learned and learned through other people, and then, really looking at people like Simon Rogan and some Asian chefs, really looking to see what they do and how they do it, and sort of learning from them, Charlie Taylor [Aulis] around the corner. Learning from them and then going, okay, well, how do we apply this to Sri Lankan food?

So that’s a very long-winded story of how I ended up in the kitchen. I now split my time 50% kitchen 50% running the business or upstairs.

T: What made you want to make the jump from corporate to opening a restaurant?

DF: I wanted to open my own business. That was the first thing. I worked in hotels for 12, 13 years and loved it. I was like, right, maybe now is the time to open my own business. The second thing is, I always wanted to open a restaurant. It was always a dream.

Opening a restaurant now, having done it, is definitely not a dream. It was more of a goal. And I never thought I’d ever open a Sri Lankan restaurant. I’d be like, no. When people said to me when I was growing up You should open something Sri Lankan, I’d be like, No, no, no, that’s not cool. Sri Lankan food is not cool. And then it came to 2017, I lived abroad for nine years before that in Dubai and Singapore, got back to London and then I took six months off, and I ate all around London. I used to sit outside Kiln and just go, let’s see what’s happening. People are really cosmopolitan in their approach to food now, especially towards Asian and modern Asian, et cetera. There is a chance to do what people like Kiln are doing for Thai Border’s food for us in Sri Lankan food. And at that point in time, it was only really Hoppers that were doing it, and even Hoppers were like more South Indian than Sri Lankan, and I just thought, okay, here’s the chance to now do something different.

I’d had the restaurant for five and a half years, and you know, we were a la carte for five and a half years, and then last year, we closed, we renovated, refurbished and reformatted our menu completely with the pure goal now of trying to progress modern Sri Lankan food. Like, really put it on the map.

T: You were saying earlier that you’re offering the first Sri Lankan tasting menu in the world?

DF: Bon Appétit said I said that we are the first Sri Lankan tasting menu in the world, and to my knowledge, that is true, right?

There are hybrids of South Indian and Sri Lankan tasting menus. There’s also a more traditional type of tasting menus, but they’re very much like rice and curry. But in terms of pure, modern Sri Lankan independent restaurants, I really believe that we were the first ones. And we’re certainly the first one in this country as well. Our goal is to, as I said, really move people’s perception away from being rice and curry to doing something else that I’m cooking. If you look at the Thais, if you look at the Indonesians, the Malaysians, the Italians, the Indians, they’ve all progressed their food culture, whereas we’re still stuck in some sort of rice and curry era. So that’s why I decided to reformat Paradise for 2.0.

T: So, how is that translating into your next concept that’s happening in Sri Lanka?

DF: We’ve learned from the last year, and I’ve learned from hospitality now, and actually, after the pandemic, the word hospitality is the most important thing, right? Because people want an experience when they go out for a meal, it’s no longer, you know, the good old days in Soho of just popping into a restaurant and then leaving and then going to pubs or bars. It still happens, but it’s definitely not as much anymore.

People are coming in for an occasion, and they want an experience. Therefore, hospitality has become increasingly important.

So, with the old Paradise, you know, we used to do 100 people in a night and sort of used to churn the restaurant, whereas now it’s very much okay, how do we tell our story? How do we give our guests an amazing experience from before they arrive, to when they get here, to after they arrive? How do we take the time to really evolve our dishes and use technique? So that’s what we spent the last year doing, and then we realised, you know what? Doing this sort of hospitality is super enjoyable. Because you can spend more time with guests as a chef, you get more time to spend on R&D and look at interesting ingredients and not just be led by GPs [Gross Profit]. And so that’s had an impact on what we want to do in Sri Lanka, which is to cook for ten people around a counter like this. And really talk to them about the ethos of the ingredients, the native ingredients, and what we’re doing with the food, what the point of view is on dishes, whether it’s like my experiences or a family dish or whatever that is, and it’s trying to, again, do something unique and new and Sri Lankan. I suppose we sort of evolved after five and a half years of having the restaurant. I’ve gone, oh, let’s open a restaurant, and now five and a half years later, I’m like, do you know what? Hospitality now is the most important thing, and it’s the all-round experience.

T: How does your relationship with All Greens affect your creativity?

DF: It’s huge, the key pillar about our brand specifically, is that it’s Sri Lankan flavours, authentic spices and flavours and recipes used with a British slant or a seasonal slant.

Whether that’s Sicilian or Mediterranean citrus during that particular part of the season, or whether it’s UK produce coming in like wild garlic or rhubarb, for example, it’s super important; it’s a key pillar of our brand. Therefore, having strong relationships with our suppliers is really, really important. We rely on our suppliers to map out what’s available during the course of the year: this is when we’re expecting stuff.

From an R&D perspective, we know roughly what’s coming up and when it’s coming up. That’s the first thing. The second thing is that when we do put something on the menu, we need it to be consistent. We need it to be of great quality, consistent with how it’s coming in and when it’s coming in. We need the price to not fluctuate that much as well because we live in a very low margin world in restaurants, especially more now than ever.

Therefore, our relationships with suppliers, looking at the entire supply chain, especially when it comes to fruit and vegetables, are of the utmost importance. It basically is what powers our business.

T: Is there anything you’d like to add?

DF: I would say that we need to, as a society, be mindful of buying in season. Right? And I think that’s maybe forgotten about a little bit. My perspective is that seasonality was really strong, and then now we kind of lost the narrative around it.

I go to New Spitalfields et cetera. I see what’s coming in, and then I speak to Rhys.

Having a finger on the pulse is important, but I think for ordinary consumers, it’s when they’re going to Panzer’s, for example, to try and buy the best British produce.

First of all, buy local, if you can, which All Greens does a great job of. And try to buy seasonal as well. It’s super important, especially with what’s going on in and around climate change and supporting our own growers is super important.

So yeah, that’s what I would say for restaurants and chefs, keep on going. You know, it is a tough time. It is a tough market at the moment. But I think that if anything, and I didn’t fully appreciate this until I had the restaurant, that this breed of people in hospitality, where they’re restaurateurs or whether you’re a chef, whether you’re a bartender, whoever it is we’ve got just so much resilience, and I honestly don’t think there’s anybody like us out there. I think in other professions, I honestly think there aren’t many that will be under the same pressure day in, day out for what we do, putting in more sometimes than what we get out.

And I think it’s just important to continue being resilient, I would say to new people that want to join the industry that we need new blood in the industry to help us push this forward I would say my only take away from the last sort of year or two is actually the move towards genuinely warm hospitality when people are paying more money, they want to have the best quality that they can possibly. They want to have the best experience. They want to have the best service.

And John Williams [The Ritz], who got two stars recently, said, You know, the chefs do what they do, but actually ultimately, it’s the front of house who delivers the service, right?

And that’s what gets you your two stars, and he’s got a point to an extent, right? The chefs are amazing, they are phenomenal, and they do what they do day in and day out. But actually, it’s brought to life by everybody who’s serving guests and giving them an experience; it’s something I believe in more now than ever before. I think that the true essence of hospitality is the most important thing.

As soon as we finish chatting, Dom disappears, running around the restaurant, receiving orders, vanishing in the maze of the back alleys of Soho. I still have to get his portrait, so I go back downstairs and observe the team hard at work as opening time is approaching.

Then Dom reappears, ready for the camera, a natural.

Want to experience Paradise’s unique take on modern Sri Lankan cuisine for yourself? Reserve a table and explore their menus here.

Photos by Tristan Benhamou.